As nurturing marine life at offshore wind farms becomes an increasing concern for developers, a global meta-analysis of research has painted a nuanced picture of whether turbines are really “oases in the desert” for fish and other animals.

The practice of converting decommissioned offshore oil and gas infrastructure to artificial reefs has been commonplace for decades in the US, which passed legislation to support this in the 1980s in response to increasing interest in fishing around the structures.

As offshore wind turbines are rolled out across the seabed worldwide, there is now mounting interest in their impact on marine life and whether they can be used to boost biodiversity.

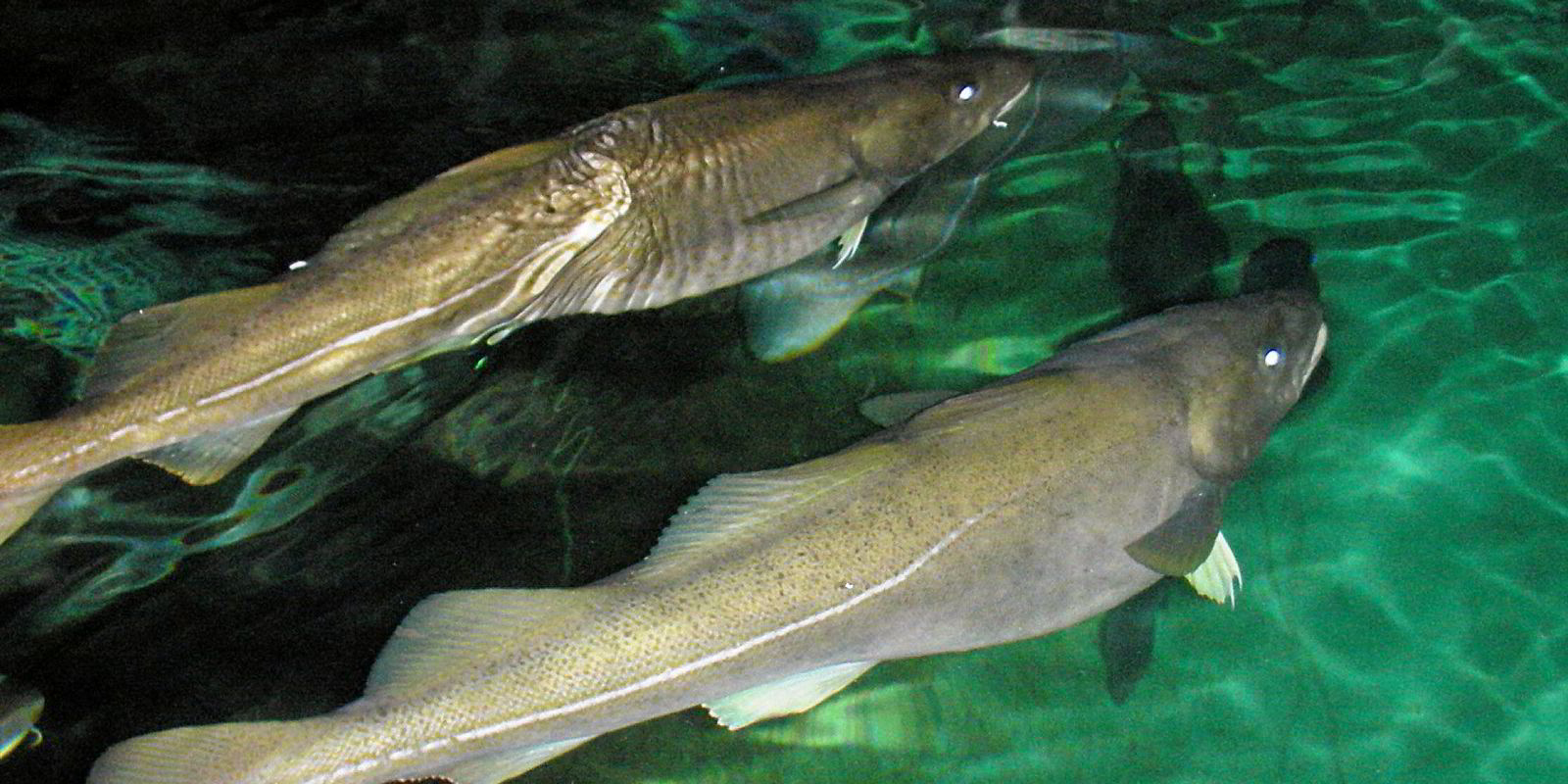

Offshore developer OX2 is investigating whether turbines could host “fish hotels” for cod, while its Swedish compatriot Vattenfall is working on how to produce sustainable foods such as algae and mussels around its wind farms.

Orsted and the World Wildlife Fund are pushing to have nature protection and restoration criteria in offshore wind auctions so that turbines have a positive impact on biodiversity, with the Danish developer currently exploring how to grow corals on offshore foundations.

Last month, a team of British and Irish researchers published a global meta-analysis in the scientific journal Nature Sustainability on how offshore marine artificial structures, namely seabed-fixed turbines and oil installations, affect marine life.

It has been argued that turbines and oil rigs could represent “oases in the desert” of sedimentary habits, which have been labelled a “sea of sand” of low diversity and ecological value compared with reefs.

Structures including turbines have “overall statistically positive ecological effects across natural sedimentary habitats,” found the researchers. “But not when compared to natural reefs.”

“Compared with natural sedimentary habitats, oil and gas installations and offshore wind farms increase fish abundance,” they said.

Such structures do not however increase the abundance of invertebrates such as crustaceans, starfish and jellyfish.

Help, hinder or neither?

The researchers found there was not more marine diversity around oil and gas installations, turbines or shipwrecks than at natural sedimentary sites.

This they said showed that only artificial reefs, which boost both fish abundance and fish and invertebrate diversity, can accurately be described as “oases in the desert.”

The researchers did however note that artificial reefs, unlike oil and gas rigs and turbines, are built in places most suitable for marine life, including shallower waters closer to shore. Purpose-built artificial reefs will also use structures and materials best suited to hosting marine animals.

“In theory,” if oil and gas installations and offshore wind farms acted as artificial reefs, the researchers said “decommissioning them by toppling, topping or reefing” could help countries hit environmental targets.

But overall, they found “limited evidence" to support the argument that abandoned oil and gas installations and offshore turbines could be used to "promote healthy productive ecosystems, and no evidence that they might benefit biodiversity.”

Efforts to repurpose such structures as artificial reefs may not therefore “provide the intended levels of benefits.”

“With that said,” there was “no evidence that reefing them would cause ‘harm’ or be detrimental,” said the researchers.

“Notwithstanding potential unforeseen consequences such as facilitating the spread of invasive species,” they said such structures could – despite their limitations – “provide a viable option to enhance ecological benefits on natural sedimentary habitats.”