Vestas CTO: 'The more industrialised we can be as a sector the bigger the role we can play'

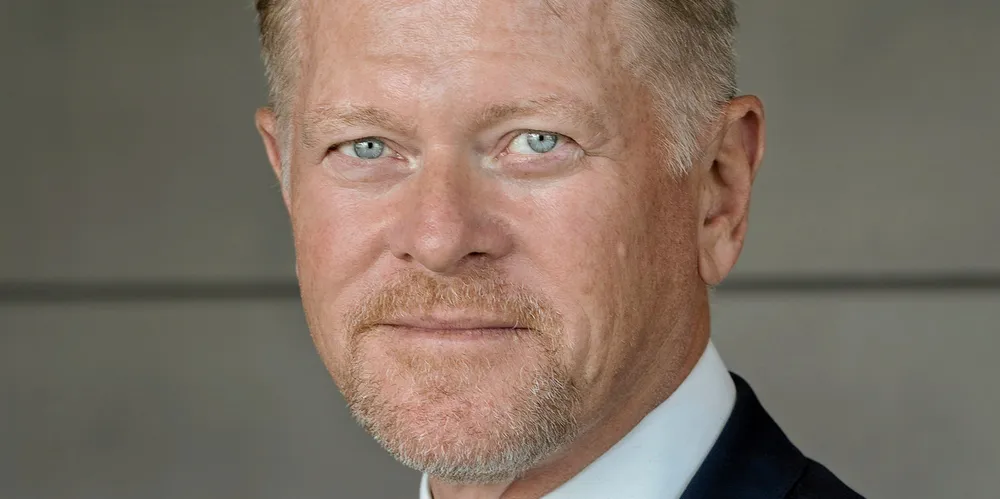

As the Danish wind giant buys out offshore venture partner MHI, technology chief Anders Nielsen talks with Darius Snieckus about innovation, the company's energy transition mission, and catching the market's 'fat fish'