Republicans' narrow House win dims outlook for new US climate measures

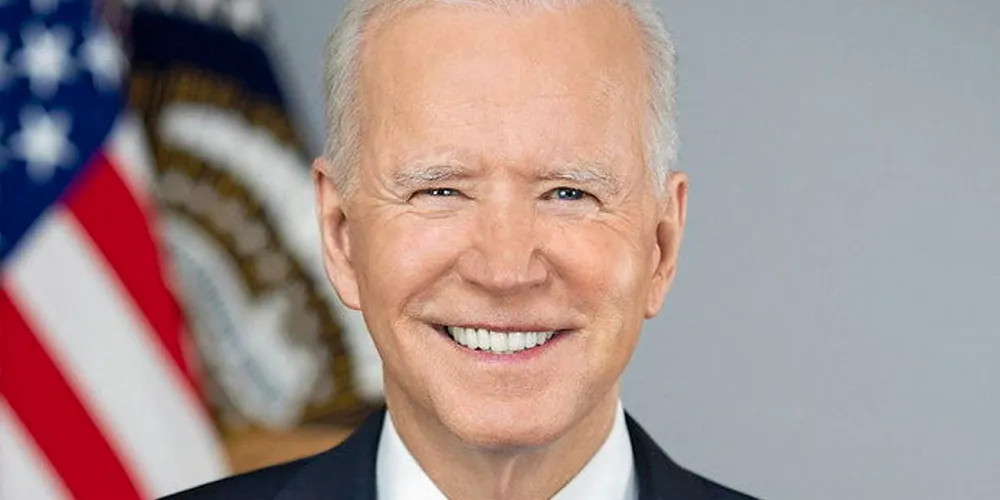

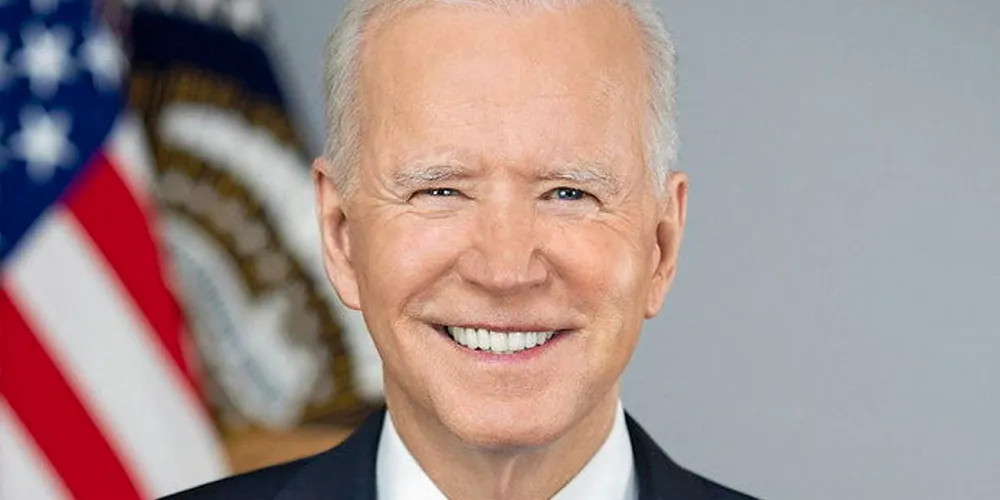

President Joe Biden has little political room for major new initiatives in the House of Representatives with opposition party soon to be the majority, writes Richard Kessler

President Joe Biden has little political room for major new initiatives in the House of Representatives with opposition party soon to be the majority, writes Richard Kessler