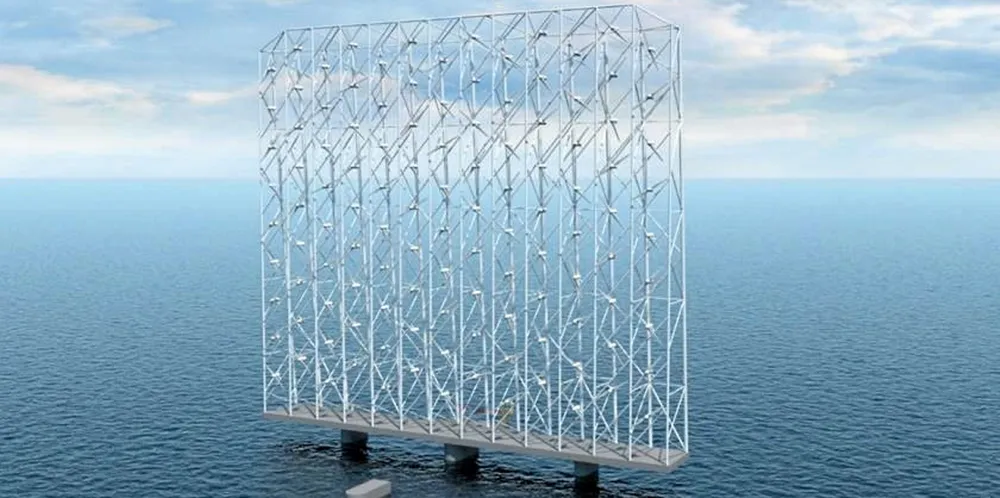

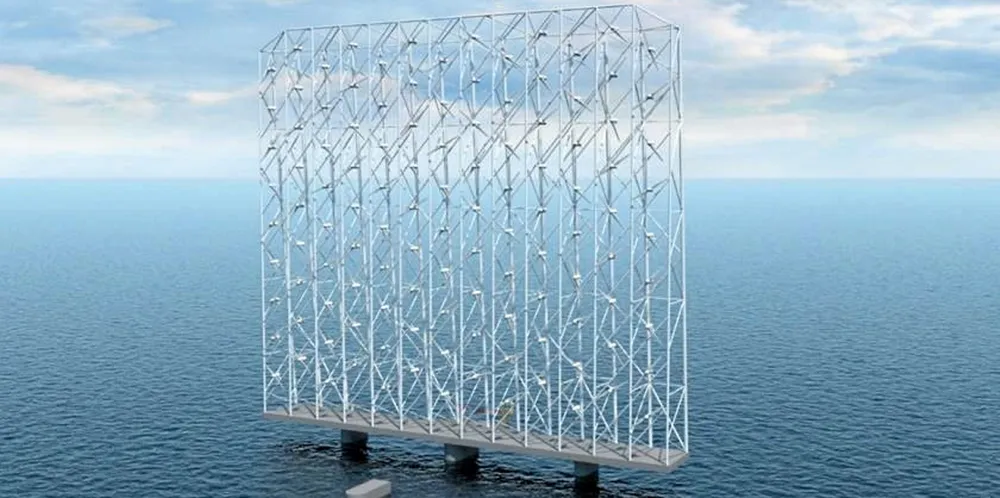

Futuristic multirotor design could make floating wind competitive 'as soon as 2022'

Norwegian outfit Wind Catching Systems calculates innovative technology would transform economics and cut offshore wind farm acreage use by 80%

Norwegian outfit Wind Catching Systems calculates innovative technology would transform economics and cut offshore wind farm acreage use by 80%