Norwegian energy giant Equinor has set the seal on forming a consortium with Korea’s state-owned oil & gas company KNOC and utility Korea East-West Power (KEWP) to develop a utility-scale floating wind farm off the city of Ulsan, with plans underway that could bring the ambitious project into production by 2024.

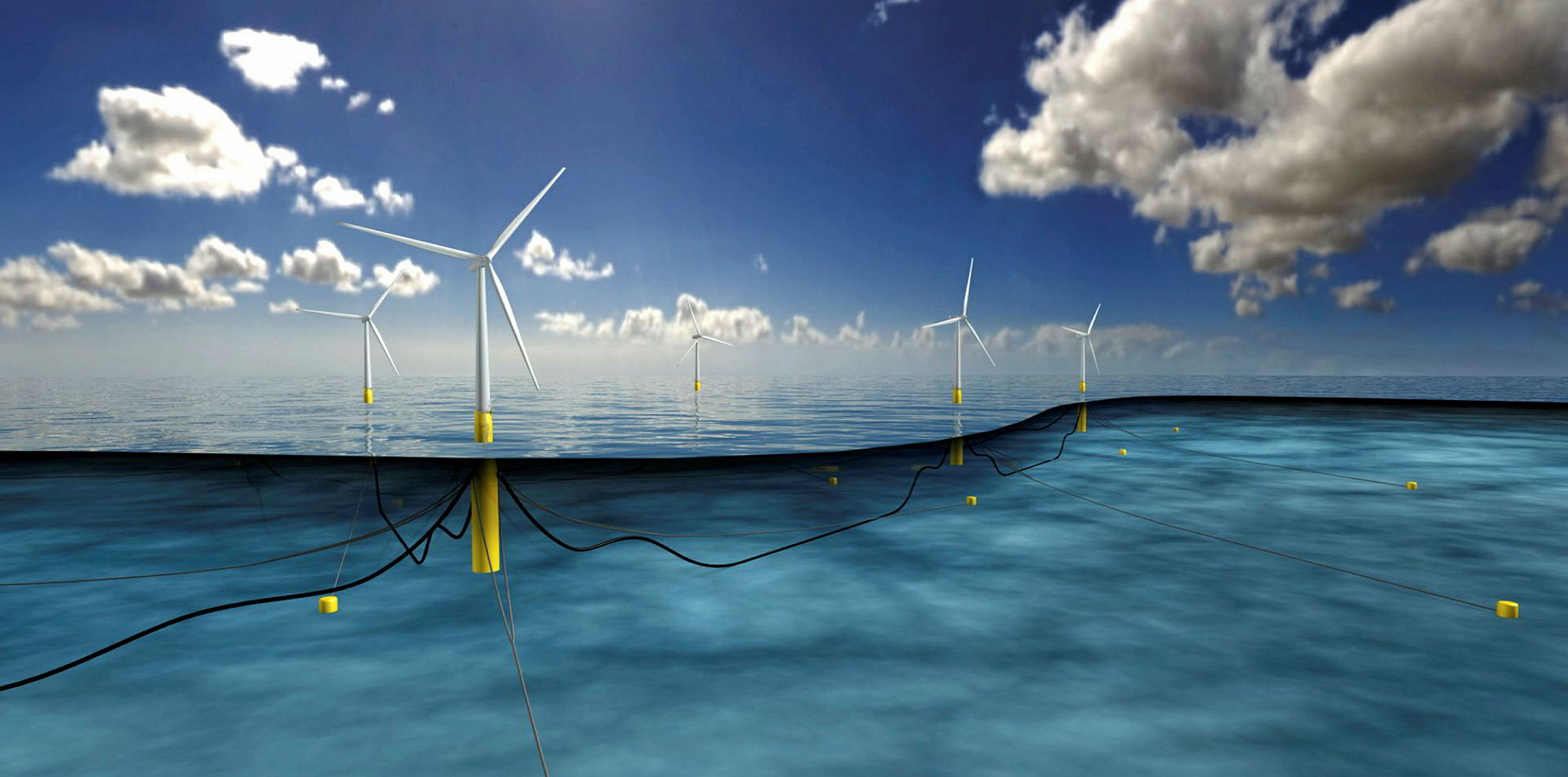

At 200MW, Donghae 1 – which will be located near a KNOC-operated offshore gas field of the same name in Korea’s East Sea and is looking to convert an existing production platform into the wind farm's substation – would be in the running to be the world’s largest floating wind development.

“We are very pleased to be member of the partnership involved in realising the first floating offshore wind farm in Asia,” said Equinor New Energy Solutions senior vice president for wind and low carbon Stephen Bull.

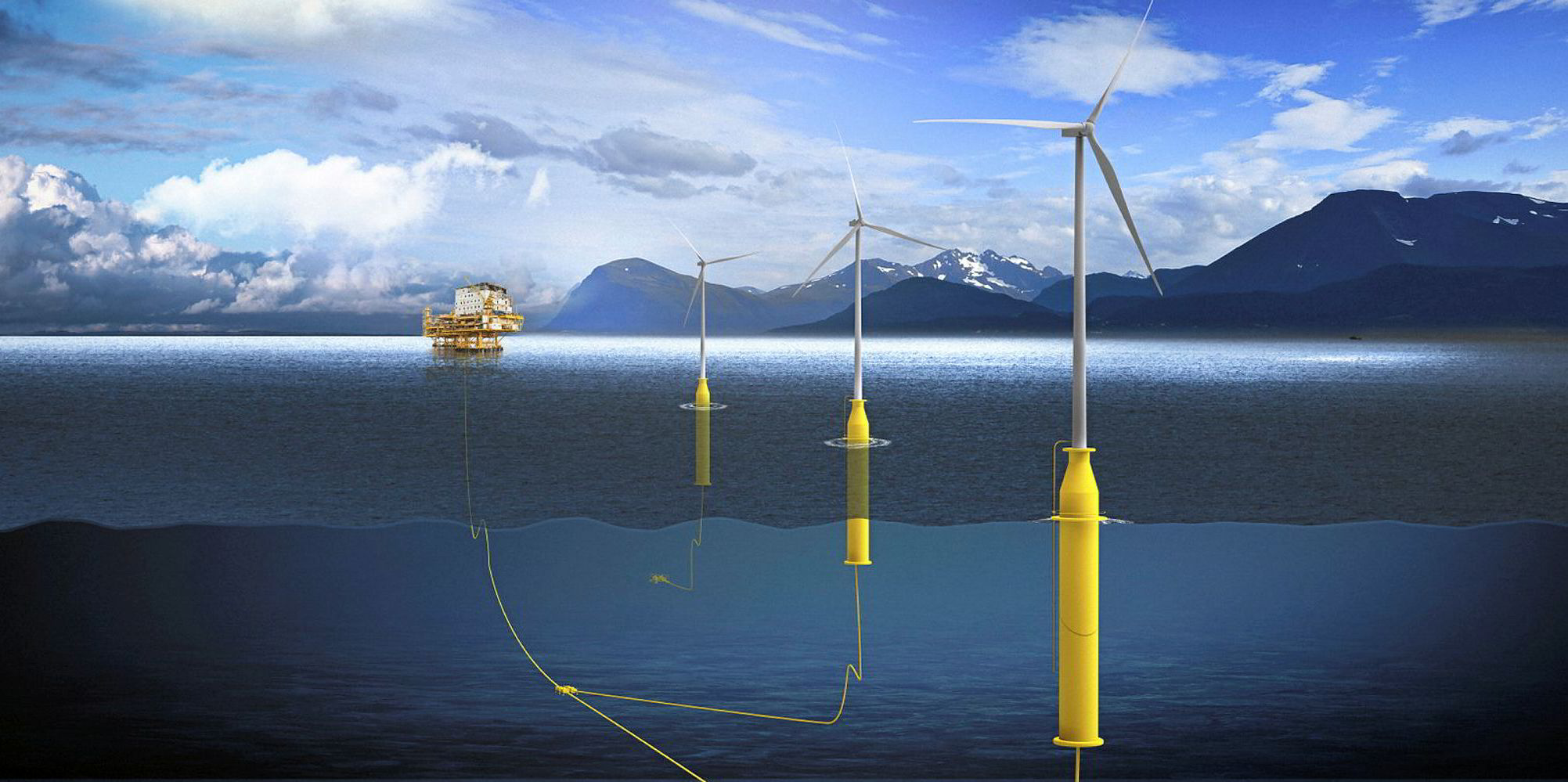

“If we succeed in realising the project, Donghae will be the world’s biggest floating wind farm, more than twice the size of [the planned 88MW floating wind / offshore oil] Hywind Tampen project on the Norwegian continental shelf.

“A floating wind farm of this size will help further increase the competitiveness of floating wind power in the future.”

The Donghae floating wind project, spurred by plans at KNOC to decommission the eponymous gas field nearby, is located in a range of water depths “in the hundreds of metres” some 60km off the island nation’s coast.

Equinor is currently “technology neutral” as to the type of floater concept to be engineered, whether spar or semisubmersible, and will lead a “six-to-eight month” feasibility study with KNOC and KEW to finalise a project development plan. Current timelines point to construction starting as early as 2022.

“Most of all we want to devise the best concept for this project and this would, of course, be in very close cooperation with Korean yards and with the local supply chain,” Bull told Recharge. “We see this project not just a chance to kick-start floating wind in Korea but also to build a base here and a floater concept that would be scaleable, potentially, across all of Asia.

“We have been working with [many of these yards] for over 20 years in oil & gas and so leveraging these relationships [to build the Donghae floating wind project] will also mean almost an energy transition for some of these yards, particularly in Ulsan.”

Bull pointed to the potential for floating wind power in South Korea as its shifts to increase the share of renewable energy in its national power mix to 20% by 2030 by adding 49GW of clean-energy to its production capacity, including 13GW of offshore wind.

“Korea is trying to phase out of coal, there are cost issues related to nuclear – the story for Korea here is one of energy transition [from hydrocarbons[ to clean electrons.”

South Korea has moved quickly in recent months to establish itself as a leading region in the Asian floating wind play, with memoranda of understanding signed early this year between Ulsan and four groups, which includes one led by oil supermajor Shell, with the aim of building out a combined 1.4GW of capacity off the island nation.

Asia is seen as central to the industrial aspirations of the rapidly emerging global floating wind sector, with analysts forecasting almost half of the 15GW expected to be installed worldwide by 2030 to be the regional market.

Last month, Japan also put its oars in the water on a first commercial-scale floating wind farm with finalisation of a deal between French technology pioneer Ideol and Japanese renewable energy developer Shizen Energy to build a “multi-hundred-megawatt” project in the East China Sea.

And in China, Recharge recently reported exclusively on plans for three floating wind pilots, the first of which, being developed by China Three Gorges, could be flowing power by 2021.

“What's interesting about developing the floating [wind] market in Asia is the uniqueness of the regional supply chain – shipbuilding but also the engineering work being done for major industrial structures such as bridges and so on, [there is] real competence and quality here,” said Bull.

“It opens up the possibility of really globalising the offshore wind market, where we are not just taking European competence straight across [to other regions]. Another growth phase is in prospect here: Europe is looking very strong, the US North-east is great, but this is a ‘third wave’ out here in Asia and could turn offshore wind into a truly global industrial phenomenon.”

As well as installing the world’s first utility-scale floating wind turbine, the 2.3MW Hywind Demo off Norway, in 2009, Equinor also brought online the world’s first floating array, the 30MW Hywind Scotland (then called Buchan Deep), in the UK North Sea.

The company confirmed in June that it had secured a permit to build a 200MW floating wind farm off Africa in waters off the Spanish Canary Islands, which according to the regional government could start operations as early as 2024.

Equinor has been a standard-bearer for floating wind power, declaring it could “outcompete” conventional bottom-fixed offshore wind by 2030.

Other old-energy giants are quickly warming to the potential of floating wind, among them French utility Engie, whose head of centralised generation, Grzegorz Gorski, claimed in April that it could do for floating what Denmark’s Ørsted — on-track to single-handedly switch on 15GW of fixed-foundation projects by 2025 — had done in the cause of conventional offshore wind’s build-out, and at an LCOE of under €120 ($134) per MWh by 2021.