Government tenders have been the backbone of growth in Brazil’s wind industry over the past decade, with their 20-year power-purchase agreements (PPAs) providing stable, healthy returns on investment. But after two years of economic and political crisis, this is no longer true: PPAs in the non-regulated market are becoming just as — or more — important in maintaining the momentum of the wind industry; it is a new landscape that developers, investors, off-takers and financiers will have to adapt to.

Almost all of the 48 projects — 1.3GW of capacity — contracted in the most recent tender on 31 August will only sell half (or even less) of the energy they generate to distributors on the regulated market. The remainder will be sold to corporate buyers or on the spot market, in the so-called non-regulated market.

This is something everybody was talking about and that now is becoming reality.

“This is something everybody was talking about and that now is becoming reality,” says Giovanni Bosco Fernandes, executive director of project finance at the Brazil unit of Spanish bank Santander. “We advised several of these projects and are preparing financing for some of them.”

Behind this trend is a rush by large and medium-sized businesses to buy the cheaper power in the non-regulated market. Even in the current economic crisis, monthly power bills have been rising by about 15% per year. For example, a business in the state of São Paulo large enough to opt into the non-regulated market — that is with demand equivalent to 3MW a year or more — pays between R$400 ($99) and R$700 per MWh in the regulated sector. By comparison, wind power sold on the non-regulated market is priced from R$160-200/MWh.

“I am starting to see small businesses pooling together to buy power in the regulated market, but most are large industries such as paper mills, metal works and chemical companies that are coming back to the non-regulated market,” says José Roberto Oliva, a partner at law firm Pinheiro Neto who specialises in the energy sector.

If opting for the non-regulated market is advantageous for off-takers, for generators it’s a mixed blessing. The upside is that it is a chance to shun the low prices on offer at the government tenders. In the August A-6 tender for example, wind power was sold at record low prices of R$90.45/MWh, with 20-year PPAs to large investor-grade power distributors. The two main reasons for the low prices were the competition from the 25GW of projects and low demand projection from power distributors.

But the downside is that non-regulated market contracts are not as long and off-takers do not have such good credit ratings. Tenures are much smaller, ranging mostly from four to seven years, although there is talk within the industry of non-regulated market PPAs edging up to ten or 15 years.

But rather than adopting an all-or-nothing approach, generators are splitting their energy between the regulated and non-regulated markets, calculating that they would complement each other and guarantee strong returns.

The strategy of mixing these two kinds of contracts became more apparent in the tiny A-4 tender held in April this year when French utility EDF Renewables secured a deal for a 114MW project at a record low price, reserving around half the power for the non-regulated market.

“We developed this new strategy when we weren’t successful in the 2017 tender [in April],” Paulo Abranches, Brazil country manager at EDF Renewables, told Recharge.

So EDF repeated the same strategy in August’s A-6 tender — reserving around 50% of the power for the non-regulated sector — and its lead was followed by five of the seven bidders.

Only Rio Energy — Denham Capital’s renewables arm in Brazil — and Elecnor’s Enerfin sold 100% and 90% respectively of the available power to the regulated market in this tender, although this doesn’t mean they won’t seek bilateral contracts, a source from one of the companies told Recharge.

The most aggressive in the split strategy were Brazilian developer Casa dos Ventos and China State Grid-controlled CPFL Renováveis: both sold only 30% of the power to the regulated market. Others allocated 40-50% of total power available for the regulated market in this A-6 tender.

As winners have six years before they start supplying to the grid, several of them are planning to kick off commercial operations in two or three years so they can sell their energy to their non-regulated off-takers and on the spot market, where prices are even higher — around R$300/MWh on average and, in some weeks, peaking at R$800/MWh when there is a scarcity of hydropower.

France’s Voltalia, for example, said it will start operating the 115MW it contracted in 2021, three years ahead of the 2024 PPA start date. Casa dos Ventos also said it would start the 33.6MW São Januário wind farm in 2020 and the 58.8MW Santa Martina in 2021.

Most of the projects are extensions of existing complexes, so will be able to use existing electrical infrastructure and grid connections, significantly reducing construction costs.

Financing

Although this all makes sense commercially, there is still the problem of financing the projects.

Since the start of Brazil’s wind industry in 2009, the National Development Bank (BNDES) has financed most of the R$60bn invested so far. The 16-year loans, with a two-year grace period, are granted after the confirmation of guarantees from project sponsors based on solid, long-term PPAs from the regulated-market tender, where the off-taker is a recognised power distributor with a consolidated consumer base and very good risk ratings.

So that begs the question: will 30-50% of the power from a wind farm be enough to raise the roughly $2m per megawatt needed to build the project?

Probably not. The BNDES has said it is ready to finance projects in the non-regulated market, but the amount financed and the cost of the loan will vary according to the quality of the off-taker and the PPA.

“This is uncharted territory, it’s not been done before in Brazil and financing will be studied case by case depending on how much will go to each market and the difference in tenures,” says Fernandes.

With BNDES financing and regulated market PPAs including inflation, double-digit returns on investments used to be the norm, but now this may not be the case.

In a one-day seminar promoted earlier this year by the Brazilian wind-power association, ABEEólica, bankers, financiers, developers and power traders discussed the issue and identified the two biggest hurdles for non-regulated market projects as the length of the contract and the quality of the off-taker.

Due to the shorter nature of non-regulated contracts, developers will have to manage several contracts, probably setting up a commercial back office to ensure constant renewal or replacement of expiring PPAs, specialists say.

But there is another inherent risk, because spot market prices are much more volatile. If prices surge when there is a scarcity of water, the opposite is true when reservoirs are full, with spot market prices falling to under R$50/MWh for weeks on end.

There are also other complex contractual issues that need to be ironed out, including how to guarantee supply when the wind is not blowing, and other more technical details. All of this points to higher financing costs, says Oliva.

So far, none of the tender winners have identified their off-takers in the non-regulated market, an important part of the equations for closing financing.

Casa dos Ventos, for example, held a private tender for wind power days before the A-6 process. But it has kept quiet about who bought the power and how much was actually sold. Abranches declined to comment on the company’s non-regulated market contracts.

Voltalia said in a release it will sell the power in the non-regulated market but also didn’t disclose to whom.

CPFL Renováveis, by contrast, invested in a non-regulated wind project in 2016, which was financed by the BNDES, but the off-taker was its sister power-trading company CPFL Brasil. The developer may also be doing the same for the 69MW project it won in August.

This could also be a solution for EDP Renewables’ 428MW contracted at the tender, since Portuguese utility EDP also controls large power distributors in Brazil.

Oliva points out that in addition to the traditional off-takers, there is a growing interest by large industrial groups to become equity shareholders in wind projects in order to supply power to their own factories.

“These large industries used to invest in large hydro projects and are now investing in wind, not only because they want to have cheap power, but because they have to comply with sustainability requirements for clean power in the statutes,” he adds, declining to name possible investors.

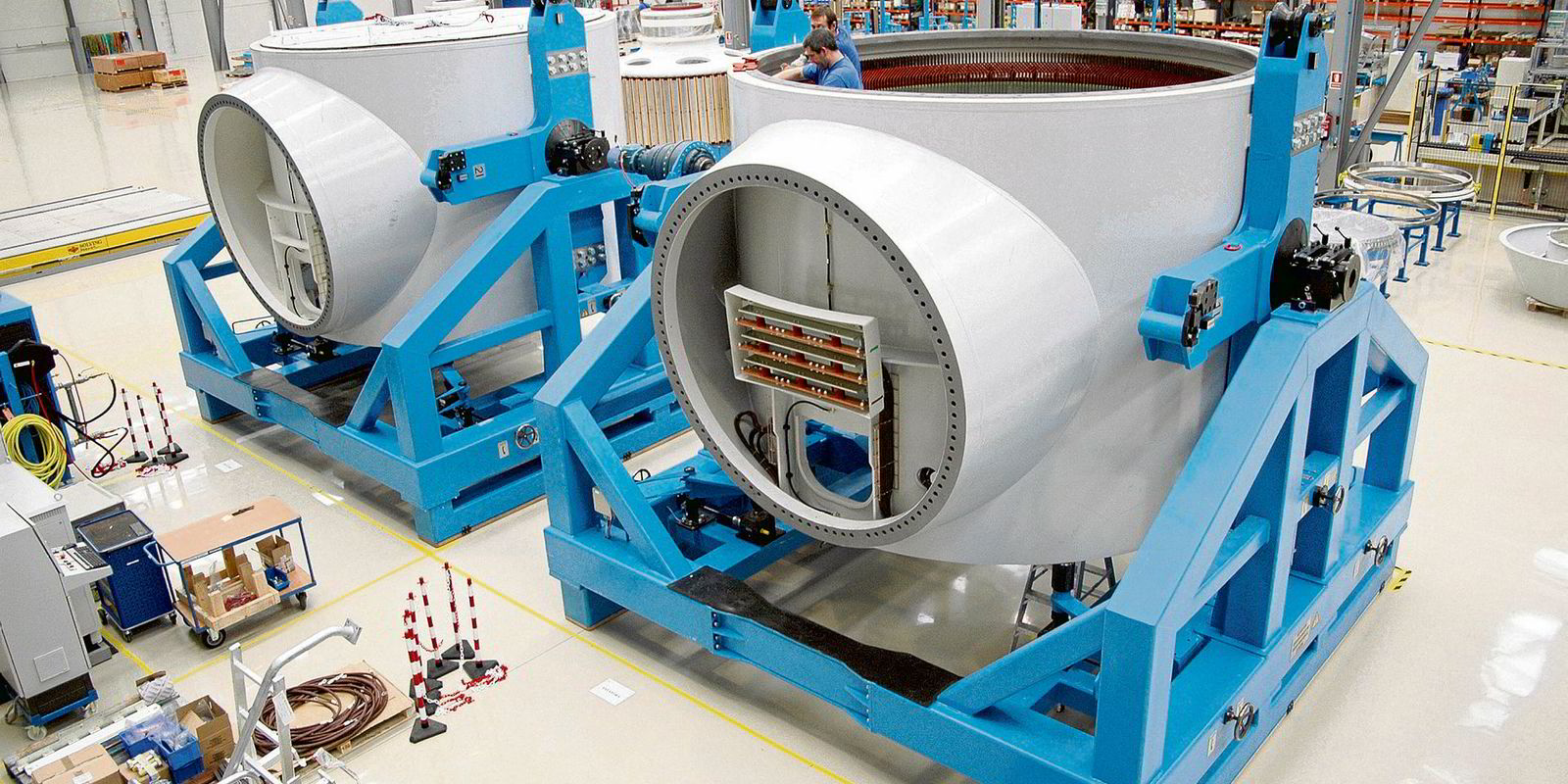

On the other hand, for OEMs Vestas, Siemens Gamesa, GE and Nordex Group — said to be the largest winners in this tender — closing the financing equation is no small matter. Until now, they have been producing 2-3MW models, but have been offering newer 3-4.8MW machines in Brazil.

If financing is secured on these projects, and many orders are placed for the larger turbines, the manufacturers will then upgrade their local factories, as well as their transport logistics, to fulfil the orders — a move that would require major investment. Their suppliers may also have to adapt their own plants to build larger components.

So not only are OEMs looking at the quantity, but also the quality of the projects’ financing, to ensure that developers will definitely have the funds to make their purchases.

For Renato Mendes, partner at the Thymos Energia consulting firm, comfort is taken from the names of the contract winners. Most are large groups with access to cheaper, foreign capital: EDF Renewables, EDPR, Voltalia, Rio Energy and Enerfin, while the two Brazilian companies are among the biggest local players in renewables: CPFL Renováveis and Casa dos Ventos.

“These companies are large enough to back these projects if they need to,” he says, indicating that he believes that not only will they obtain the financing in the end but that the projects will start construction before they close financing for the project, or if only part of the project is financed.

The coming weeks and months will reveal if Brazil’s wind industry has managed to wean itself off government contracts and diversify into the uncharted territory of non-regulated market contracts and financing.

Fernandes, for one, is optimistic. “There’s no reason not to finance a good project,” he says.

![]()