Time for Big Oil to put its money where its mouth is over energy transition

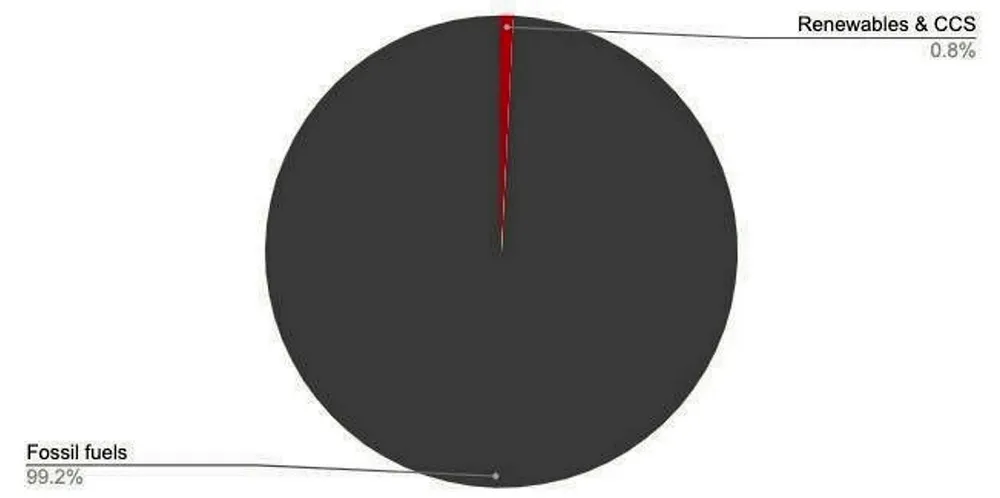

With a share of total investment in renewables that's still woefully low, the fossil fuel sector needs to lead the world's clean energy shift from the front, writes Darius Snieckus