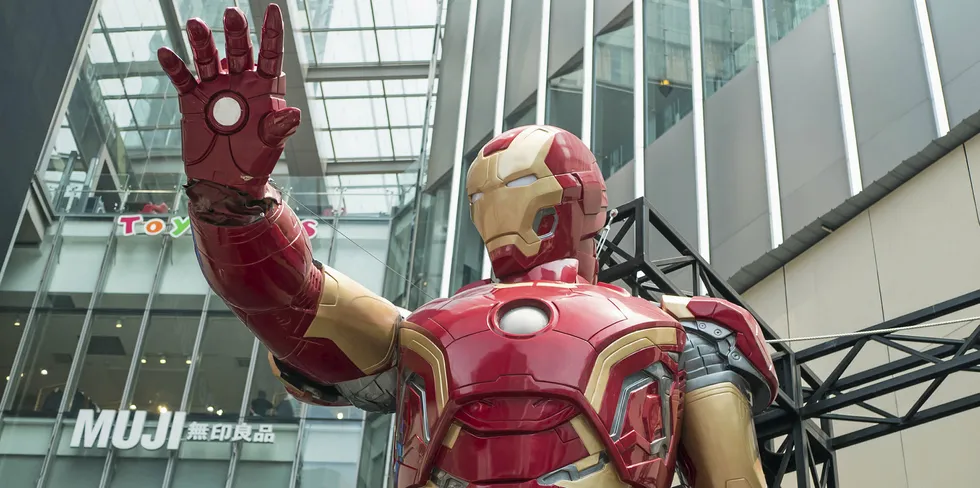

Offshore wind needs Iron Man 'digital superpowers' for heroic challenge of global build-out

Marvel character's ability to integrate vast quantities of data shows how digitalisation can transform industry from turbine engineering to O&M, Recharge event told