Whether in the form of power bills, windfall taxes, North Sea oil licensing or shale gas fracking, energy loomed large over Liz Truss’ short, shambolic term as UK Prime Minister – and as in other areas of policy, too many of her calls were the wrong ones for a nation with net zero ambitions in the early stages of a green transition.

Truss – who took over as leader of Britain’s Conservative Party from Boris Johnson and was named Prime Minister on 6 September in one of the last acts of the late Queen Elizabeth II – stepped aside today (Thursday) as her government spiraled into chaos after her flagship tax-cutting economic agenda fell apart under pressure from global financial markets.

A bemused, angry UK public now faces the prospect of another unelected – except by its own MPs and members – Conservative Prime Minister being foisted on it, with no sign that the party will give in to calls for an immediate general election that would without doubt see the opposition Labour Party sweep to power.

It was fitting that the final straw for Truss’ leadership, the shortest in UK history, came in a late-evening parliamentary vote yesterday over measures her government brought forward to lift a ban on shale gas fracking, with scenes of uproar in the House of Commons and allegations that Truss’s aides had bullied wavering MPs into backing the measure.

Ending the fracking ban was one of a series of energy-related policies and pressures that helped to define Truss’ 44 days in charge.

Energy is top of the agenda for national leaders the world over, and like peers elsewhere in Europe Truss rapidly unveiled a costly support plan to shield consumers from the worst of the price rises unleashed after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

So far, so good, but Truss’ policy stance since she came to office was eye-catching for many of the wrong reasons, at least from the point of view of clean energy and renewables advocates.

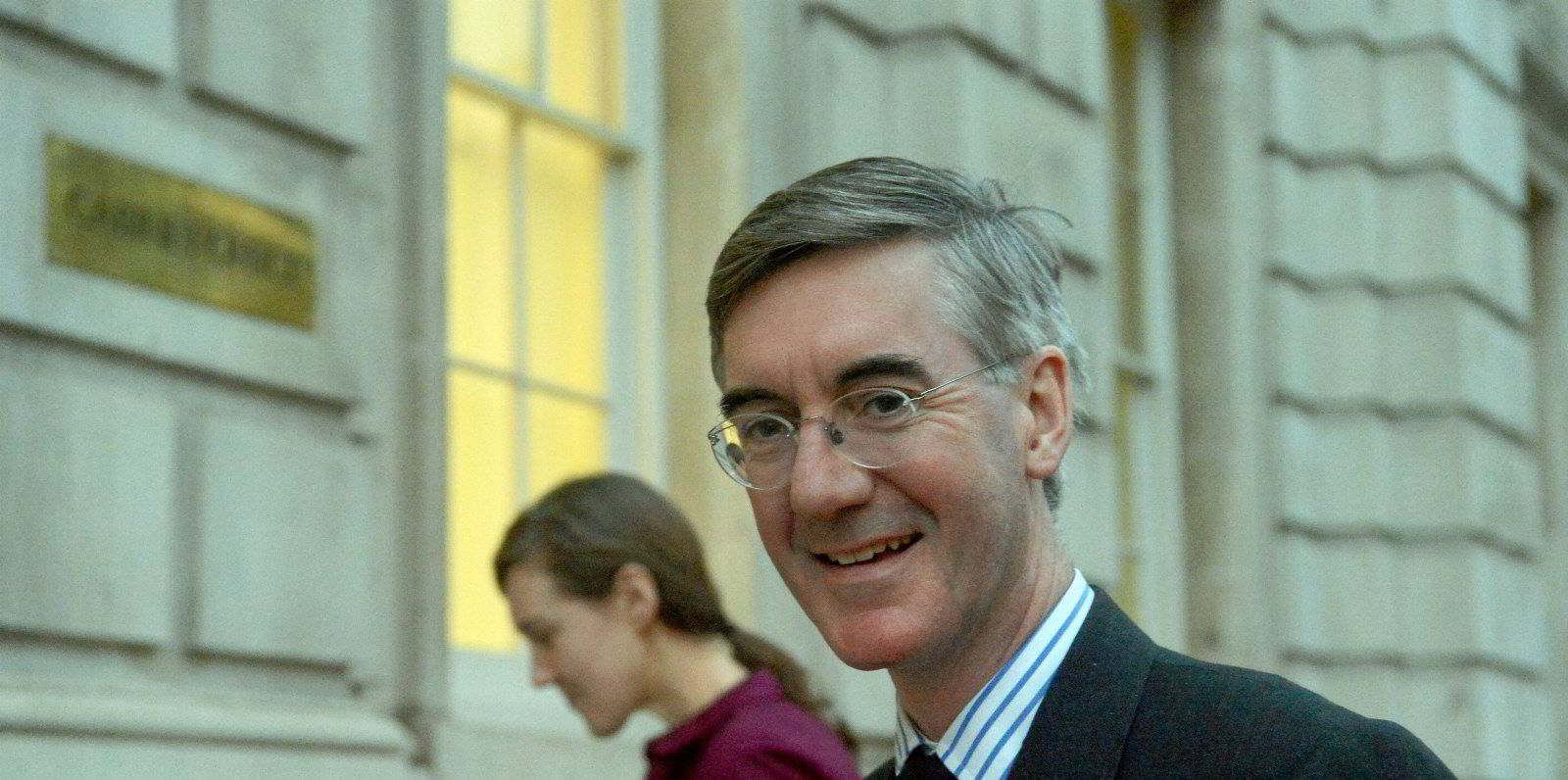

An early warning sign came from her appointment as energy secretary of Jacob Rees-Mogg, a famously eccentric Conservative politician described as a “climate dinosaur” by opponents who has previously urged the UK to squeeze the North Sea dry of oil & gas. (As a side-note, Rees-Mogg’s predecessor and until recently a familiar face at British energy industry events was Kwasi Kwarteng, Truss’s long-standing friend and neighbour who she promoted to chancellor of the exchequer, the government's top finance minister, and whose bungled 'mini-budget' almost blew up the British economy.)

A Truss energy strategy was drawn up that confirmed many of the worst fears of those who predicted the new team at the top of the UK would be bad news for the green agenda, with one big positive – a u-turn on punitive planning laws restricting onshore wind in England – drowned out by the negatives.

A new North Sea oil & gas licensing round was announced, less than a year after the UK hosted COP26 and in direct opposition to warnings from the International Energy Agency that nations need to stop all such fresh activity if climate doom is to be avoided.

Unlike the opposition Labour Party policy, and her predecessor Johnson, Truss signaled there would be no additional windfall taxes on oil & gas giants to help pay for her energy support measures.

Renewable generators would, however, face what the green power sector labelled a “de-facto windfall tax” of their own – although the announcement of the policy contained no clue as to where a price cap would be set, in stark contrast to the clarity offered by the EU. That led utility giants such as RWE and SSE to warn darkly over the need not to imperil crucial investment in the UK’s power system.

Truss also seemed to have a long-standing, almost personal aversion to putting solar modules on farmland, to the ire of a PV sector that warned she was needlessly imperiling 30GW of badly-needed power capacity.

And then there was the fracking issue that led one of Truss’ own MPs, Chris Skidmore – who the now ex-Prime Minister personally appointed to lead a review of net zero policies – to join the growing ranks of his colleagues in signalling his displeasure by refusing to back the lifting of the UK’s shale gas moratorium.

Skidmore said: “As the former energy minister who signed net zero into law, for the sake of our environment and climate, I cannot personally vote tonight to support fracking and undermine the pledges I made at the 2019 general election. I am prepared to face the consequences of my decision.”

As it turned out, it was Truss who faced the consequences the next day.

How much of her energy agenda survives under whoever becomes Prime Minister next won’t be known until they take office.

One thing is clear, however. As an economy that needs massive investment in onshore and offshore wind, power networks, storage and a barely-started hydrogen infrastructure, the UK energy sector – just like the nation’s weary electorate – badly needs a period of orderly calm under a leadership that makes more right calls than wrong.