'Not a ton of time left' | Clock ticking louder on Biden's bid to pass key US climate bill

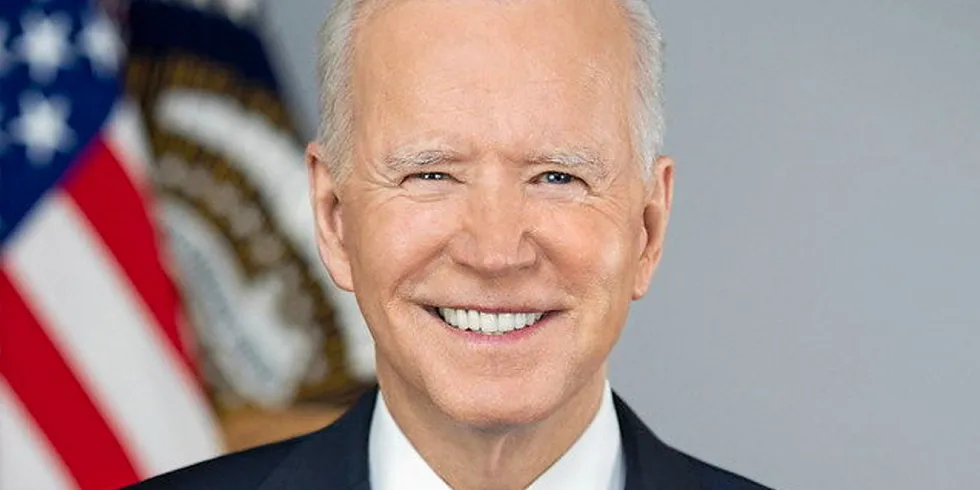

With elections looming and Democrats in control of the levers of government, this is likely Biden’s last chance to get significant legislation across the finish line, writes Richard A Kessler