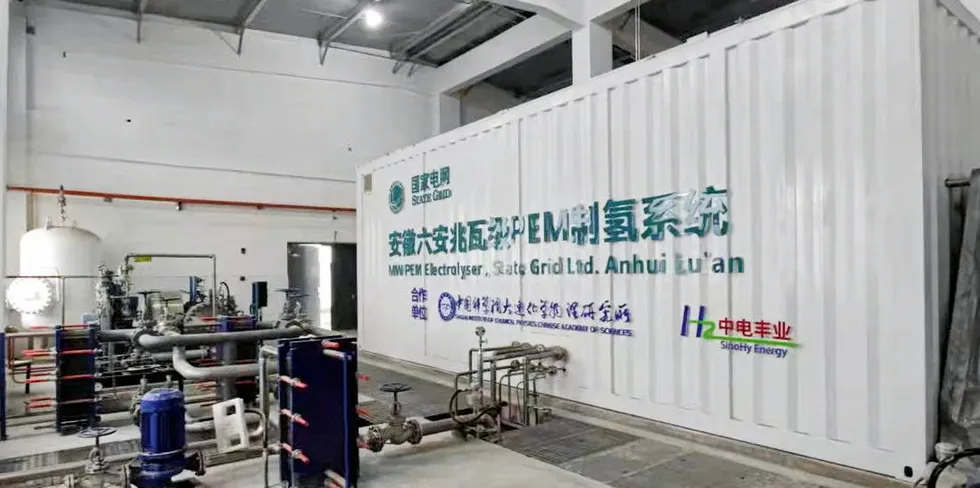

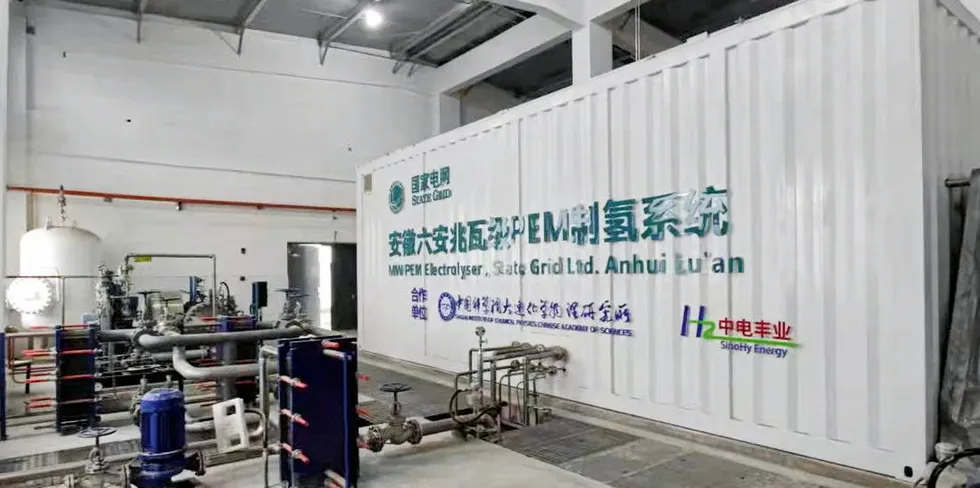

EXCLUSIVE | 'Chance is high that China will take over global hydrogen electrolyser market in similar way to solar sector': BNEF

Chinese machines cost 75% less than Western equivalents — and are just as efficient, analyst Xiaoting Wang tells Recharge

Chinese machines cost 75% less than Western equivalents — and are just as efficient, analyst Xiaoting Wang tells Recharge