Denmark has set a new goal to produce 4-6GW of green hydrogen annually by 2030 — one of the highest targets in Europe — and will also hold a DKr1.25bn ($184m) tender for renewable H2 production.

The primary aim of the new policy is to produce green fuel from the hydrogen to power aircraft, ships and trucks — a strategy that has taken on new urgency after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The plan had originally been announced in January, and will now move forward after the minority Social Democrat government won backing from all the major parties in the Danish parliament. Such support makes it extremely unlikely that a future government would overturn the agreement.

Climate and energy minister Dan Jørgensen said that the deal will ensure that the country can be a leader in the move away from fossil fuels, and help make Europe “more independent of Russian black energy”.

The Danish government said the 4-6GW target will produce about two million tonnes of green hydrogen per year, and added that it will present a plan to ensure that Denmark will be a net exporter of green energy, taking into account the new Power-to-X (PtX) goal.

On top of the DKr1.25bn tender — which will essentially subsidise the production of e-fuels for ten years — regulatory frameworks will also be amended to make PtX more attractive.

Measures will include reducing electricity tariffs for green fuel producers; the opportunity to run power lines directly from wind and solar farms to PtX systems; the setting up of a new DKr57m “PtX task force” to guide authorities and project developers; and a “first step” towards establishing H2 infrastructure that can promote exports to Germany and beyond.

“With the new agreement, we remove the known barriers to large-scale PtX, and pave the way for the production of new green fuels and a better and more flexible use of our energy system,” said Anne Paulin, climate and energy spokeswoman for the ruling Social Democrats.

The agreement does not appear to define “green fuels” or “PtX”, but it does refer to ammonia, methanol and “e-kerosene” — the latter being chemically identical to existing jet fuel, but produced by combining green hydrogen (derived from electricity, hence the “e-“) with captured carbon dioxide.

Hydrogen itself can also be considered to be a green fuel for trucks and possibly short-distance airplanes and vessels, while ammonia and methanol — both derived from hydrogen — are being discussed as potential shipping fuels. Other potential green fuels include e-methane, synthetic petrol and e-diesel.

All of these e-fuels will be far more expensive than fossil fuels due to their high production costs, the inefficiencies of the conversion processes and the huge amounts of electricity required to power them (which would need to be renewable to ensure significant greenhouse gas reduction).

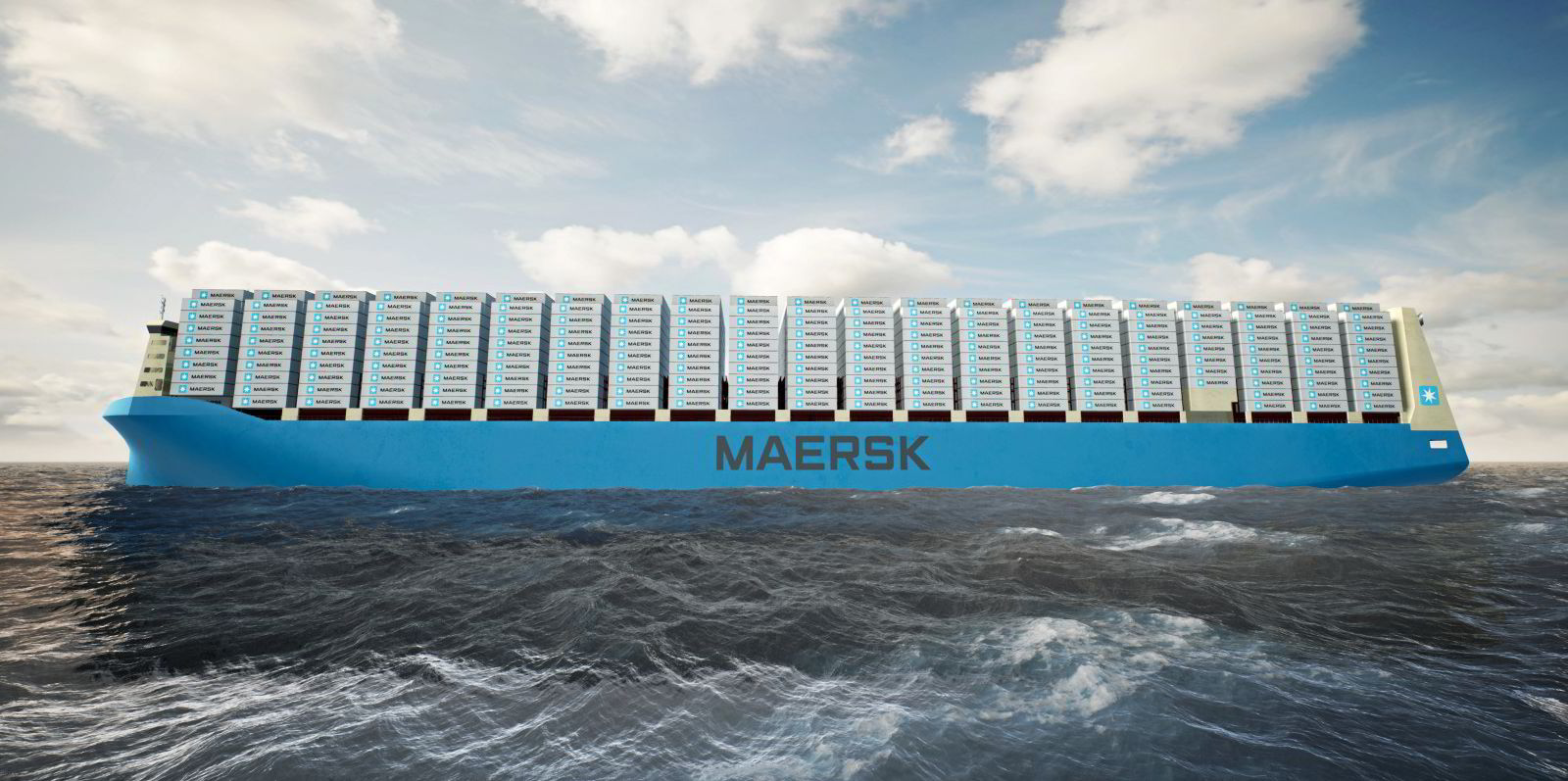

Nevertheless, the Danish shipping giant Maersk has ordered 12 dual-fuel container vessels from Korean shipbuilder Hyundai Heavy Industries that will be able to run on methanol (CH3OH), and just last week announced deals to source at least 730,000 tonnes of green methanol (derived from renewable H2 and captured CO2) by the end of 2025.

The government agreement also comes a day after Frederik, the Crown Prince of Denmark, launched Danish outfit Stiesdal Fuel Technologies’ new demonstration plant for carbon-negative aviation fuel derived from agricultural waste. The technology is carbon-negative because it uses the CO2 captured by plant matter as it grows, and turns it into a solid carbon called biochar — essentially removing the greenhouse gas from the atmosphere.

The Danish government has an ambition to use e-kerosene, or synthetic aviation fuel, on at least one domestic flight route by 2025.