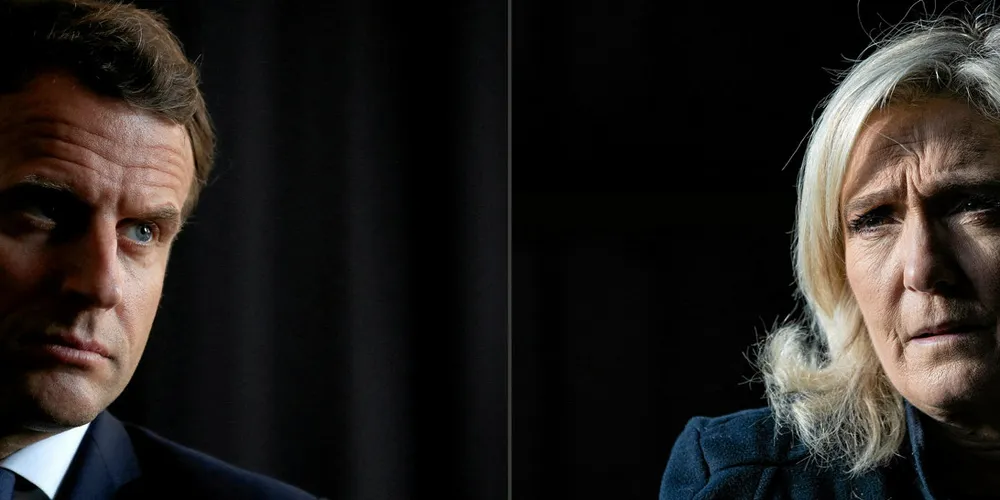

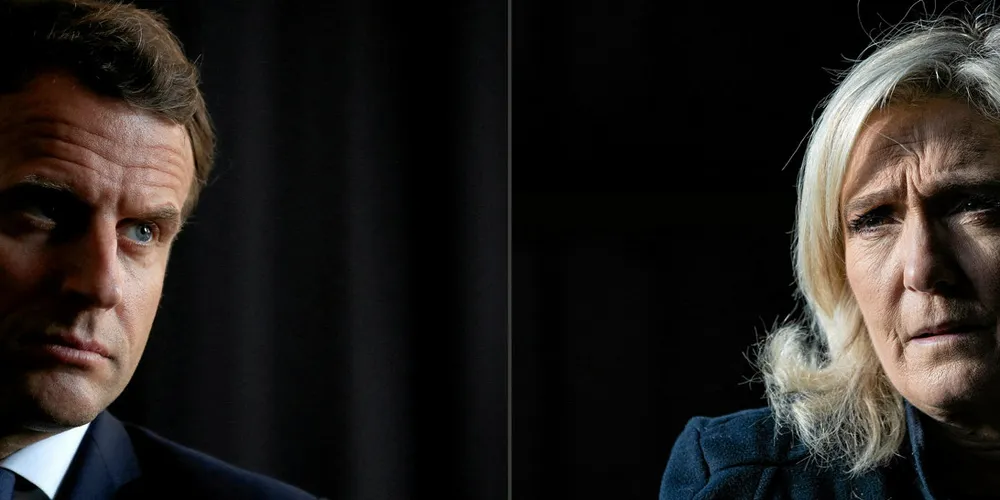

Wind power needs a Macron victory in France – but even as a loser Le Pen's done damage

THE RECHARGE VIEW | The incumbent president is leading his far-right rival but the threat to renewables expansion won't vanish on Sunday, writes Bernd Radowitz

THE RECHARGE VIEW | The incumbent president is leading his far-right rival but the threat to renewables expansion won't vanish on Sunday, writes Bernd Radowitz