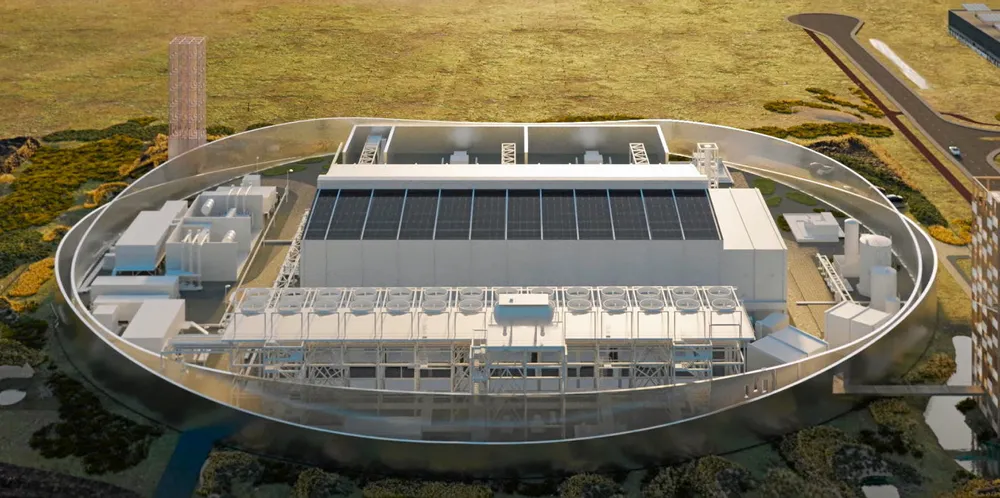

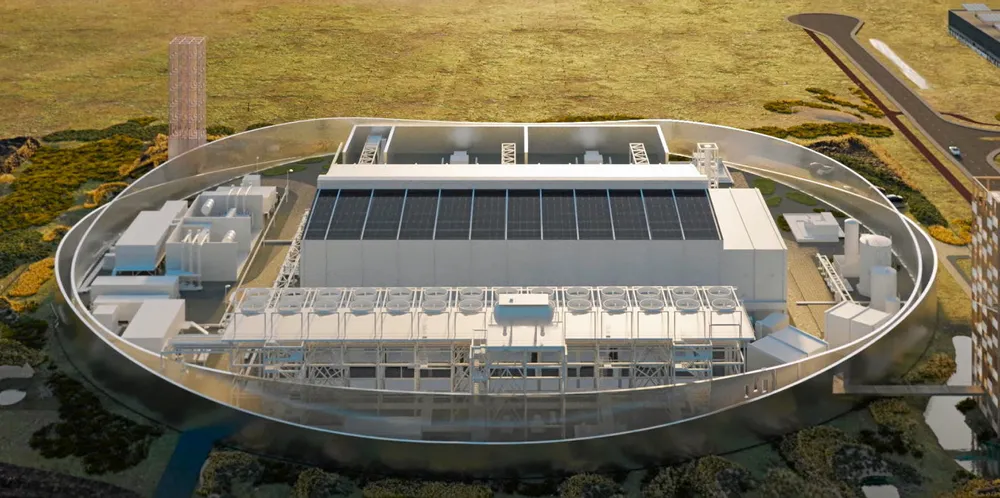

'Takes guts' | Shell gives green light to 200MW Dutch green hydrogen project powered by offshore wind

Final investment decision made on Holland Hydrogen 1 project despite unclear regulatory environment and zero subsidies

Final investment decision made on Holland Hydrogen 1 project despite unclear regulatory environment and zero subsidies