'It's time to talk about why deep-sea mining is crucial to the energy transition'

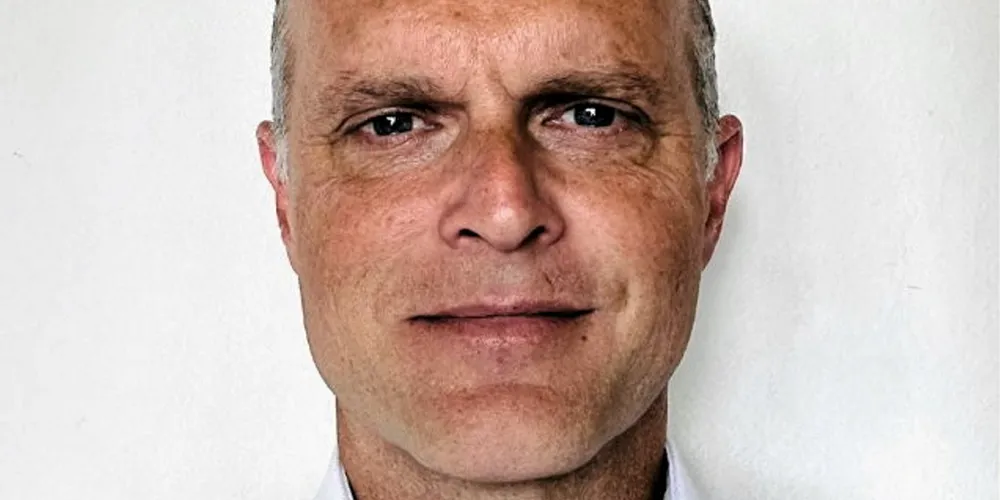

OPINION | Opponents don't want the conversation to start, but seabed extraction of critical minerals could transform the prospects for green industries, writes Michael Morris