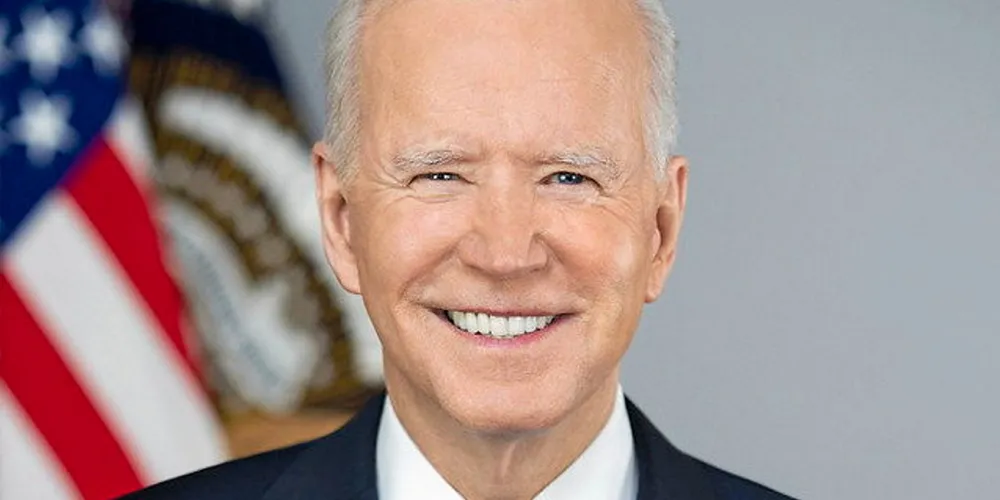

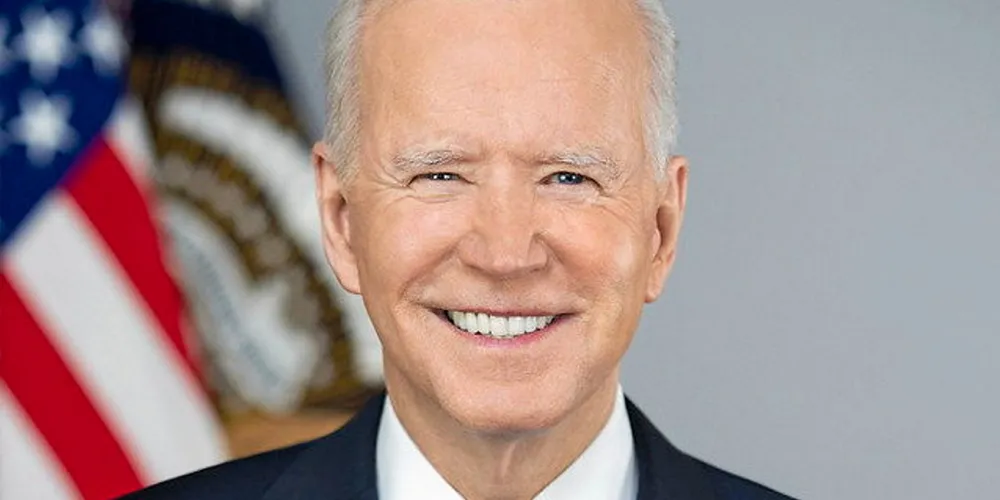

Inside the IRA | What Biden's big green giveaway means for US renewable energy

IN DEPTH | The act Biden calls 'the biggest step forward on climate ever' will be decisive to the President's ambitious decarbonisation agenda, writes Richard Kessler

IN DEPTH | The act Biden calls 'the biggest step forward on climate ever' will be decisive to the President's ambitious decarbonisation agenda, writes Richard Kessler