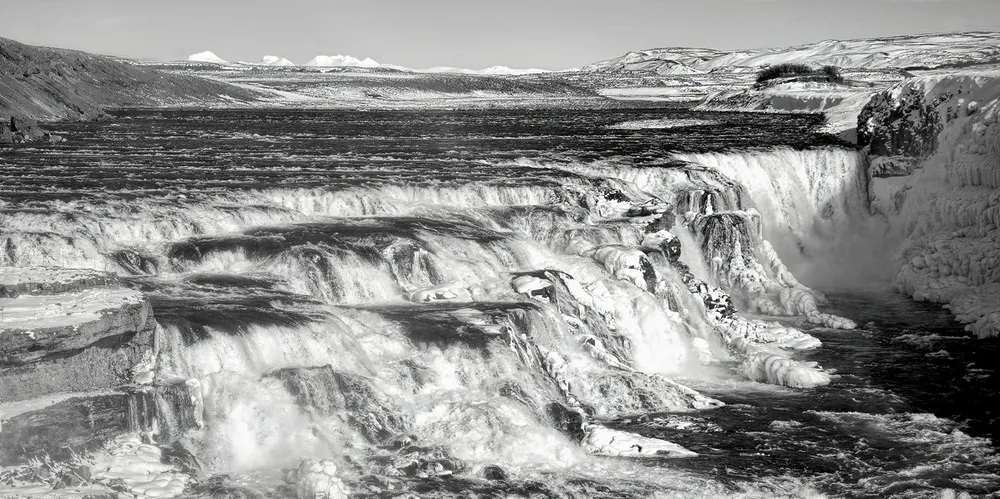

‘Absolute science fiction’: what's next for $80bn green plan to supply a quarter of Africa's power?

Colossal hydroelectric project could provide transformative amounts of electricity for Africa but securing backers is among many challenges ahead

Colossal hydroelectric project could provide transformative amounts of electricity for Africa but securing backers is among many challenges ahead